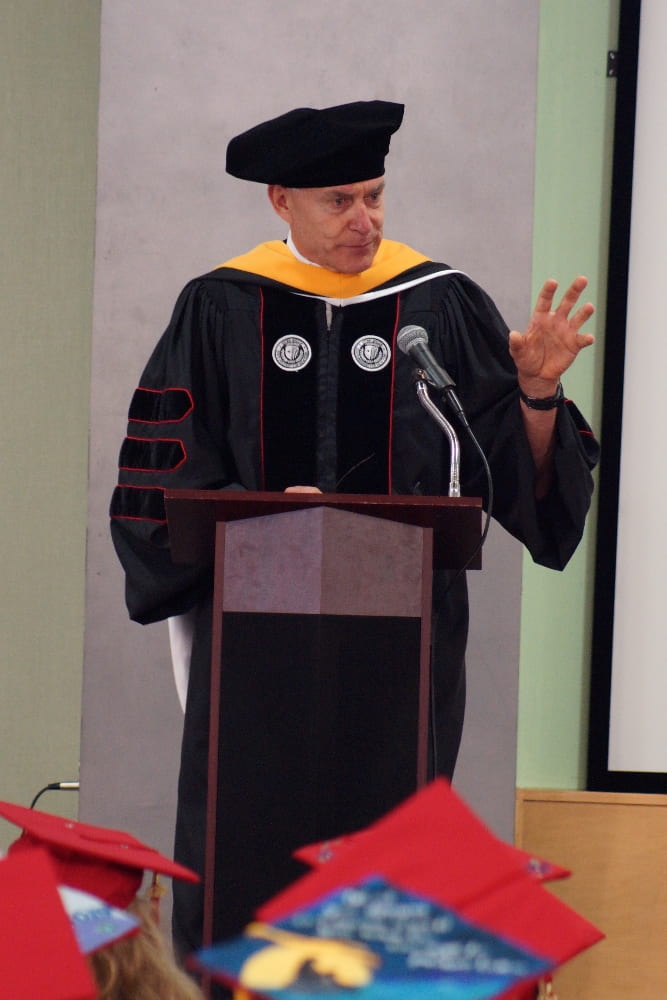

Greg Marshall (PhD, 2019)

Imagine being underwater and seeing a shark swimming nearby.

What would go through your mind? Fear? Wonder?

When Greg Marshall ’88 saw a shark in the water near him off the coast of Belize in 1986 — while doing research for his master’s in Marine Science at Stony Brook University’s School of Marine and Atmospheric Science (SoMAS) – he was struck by inspiration. That inspiration would lead to a career with National Geographic, two Emmy Awards, and, at Stony Brook’s 2019 Commencement, an honorary degree.

The inventor of the Crittercam, a non-invasive camera that allows researchers to record animal behavior in the wild, Marshall was presented with an honorary Doctor of Science at the Doctoral Hooding ceremony on May 23. Prior to the ceremony, he discussed Stony Brook’s influence on his career, his work with National Geographic, and his experience returning to campus as the Akira Okubo Visiting Scholar in 2017.

What does it mean to come back to Stony Brook to get an honorary degree?

As you can imagine, it’s amazing. I’m completely thrilled, and a bit overwhelmed. It’s such an incredible honor, and I suppose I think of it as the cherry on top of having an interesting career that started here 30 years or so ago. I didn’t go the academic route and pursue a PhD, but the fact that it’s come back to this is really a wonderful culmination of 30 years of hard work and a pretty fulfilling life.

Are you going to insist that anyone call you “Doctor?”

Are you going to insist that anyone call you “Doctor?”

Of course! I’ve got my kids calling me “Doctor” already!

Actually, I’m a pretty casual guy, so I’m not going to insist on anything, but it would be a very nice little treat.

You mentioned that your career started here. Take us back 30 years or so. What brought you here?

I’d finished my undergraduate degree in 1981 at Georgetown, and I had thought I’d go to law school. I was prepared to go to law school — I was interested in international law — but I thought I’d take a couple of years to explore other things as well. I was interested in photography and journalism, so I moved to New York City and explored photojournalism. At the end of a year and a half, I decided, “Well, this probably isn’t for me, and I’m still not that interested in law school” — my dad’s a lawyer, so law school had always been part of the equation. But, I just wasn’t passionate about it, so I made a list of things that I was passionate about. No matter how I parsed that list, marine biology was on top. I thought, “I’m 28 years old. I’m young. Why not give it a shot?” So, I decided to find the closest marine science program that had a good reputation, and Stony Brook was at the top of that list. I came out the next day to talk to people, and brought my academic records with me. What I heard was, “You know, you’re well prepared for law school, but you’re not ready for marine science. You’ve got a lot of work to do to get into this graduate program.” They outlined what I needed to do: physics, chemistry, calculus, and all these things that I hadn’t focused on in college. I was told, “If you can do this, and do it well, then we’ll consider you.” The following year I spent here at Stony Brook doing those core undergraduate courses. When I finished I came back to the Marine Sciences dean and said, “Well, we talked a year ago, here’s my transcript for the things you told me I needed to do. Now, what do you say?” He looked at it, and said, “I told you this is what you needed to do, and you’ve done it, so welcome aboard.”

This was my passion, as it had been since I was a kid. It’s great that my brother came for the Doctoral Hooding ceremony, because it was really he and I together, out exploring in the ocean, snorkeling together, diving together that really nurtured the passion I have for the ocean. So, finally I was here, pursuing something that truly inspired me, and I remember this incredible feeling of satisfaction and completeness. I remember walking back from class one day feeling “This is where I should be. This is right.” It was a really fulfilling, complete feeling. As it turns out, the rest of my career happened by good fortune and some, of course, preparation to be lucky. I was fortunate to have learned some of the skills and background I needed to ultimately have a life changing encounter with a shark which opened my eyes to new research possibilities.

Let’s talk about the shark.

I was a student here, pursuing my master’s degree, but doing my actual physical research in Belize. I was diving for the research, and out there one day and had an encounter with a shark. I’d had others, but this one was a unique experience for two reasons. First, I’d just built an underwater camera for a film I’d decided to make about the research I was doing and the problem that I was trying to solve (at the time I was dealing with the demise of the queen conch populations in the Caribbean as a result of overfishing — and I made the film from the locals’ perspective about their overfishing of this critical resource). I didn’t have any money, so I had to build my own underwater camera which enabled me to make the film which generated money for marine conservation in Belize. So, the whole concept of filmmaking and conservation came together at that point in my history. So, I’d just built an underwater camera system, and it occurred to me the moment I saw a remora, a suckerfish, suckled onto the belly of the shark, “The camera that I’ve just built is about the same size as that remora, and if I streamline my camera, I wonder if we could ride along with the shark. The shark might not change its behavior, because it’s used to having a remora ride with it. We could learn amazing new things about sharks’ behavior and ecology.” That was the moment that my life changed course again. That was the start of the Crittercam. I thought, “Surely, someone’s done this,” but discovered that no one had, and I became passionate about trying to make it happen.

I came back to wrap up my degree here, write my papers, submit my thesis, and while doing that, I decided to see if National Geographic would be interested in my idea. I called them up, and they agreed to have me come by and talk. Well, they were gracious, saying “Yeah, interesting idea, but we don’t fund ideas that are quite this new and untested.” So, it took another five years of really intensive work on my own, with some little grants here and there — including one from Stony Brook — before I got my first grant from National Geographic in 1991. The next year, I secured another grant from Geographic, and they said, “This is interesting; you’re proving this thing.” Following that I starting contracting with them then joined the staff a year or so later. I was staff for the next 23 years in various capacities: I was a scientist/specialist, then executive producer, and ultimately vice president.

What was the first footage that you got that made you say, “Wow, I’ve really got something here?”

The very first footage was from that captive animal in Belize, a sea turtle. What was interesting about that was that the turtle behaved normally, and all the other animals in the pen with it behaved normally. It gave me confidence that this system had potential, because the animal itself didn’t behave differently, and the other animals it was interacting with didn’t behave differently, so it gave me the sense that there was real potential for doing good science.

Then in 1992 or 93, National Geographic decided to make a film about me and my early efforts, and they captured the moment on film of us seeing the first images from a wild, free-ranging animal in its natural habitat — a tiger shark. That moment was just spectacular. It was years of commitment, belief, and rejection and work, wrapped up in a moment where we finally see the world from from a wild, free-ranging animal perspective and I realize this is going to work. It was extraordinary.

If you go to drama school, you may think that maybe, one day, you’ll win an Emmy. You go to film school, maybe you think about winning an Emmy. You go to school for marine science, you don’t think about winning Emmy Awards. What did it mean for you to win those two Emmys?

It’s fun, obviously. You stand up there, they call your name, and you think, “Really?” There’s that moment, which is incredible.

In terms of the meaning, it’s bit more complicated. The award itself is fantastic. That part of it, to be recognized, contributing something unique and new in the film world, is terrific. I love it. But it became a bit of a professional challenge because the images are captivating and people in the media world began to think of this as media and not science. They would say, “These are cool images, and we should get more cool images for film.” Problem is, my primary objective is science and research.

I began to get calls from producers saying, “We’ve got to put cameras on the back of X, Y, and Z,” and I said, “Well, we could, but we’re working with animals and will only do so if there’s a good scientific rationale for it.” If we get great images that can be used in films and stories, fabulous, but our primary objective will always be science and research, and if that’s not the primary objective, I’m not interested.

Media and its impact in conservation are critical. My concern was the potential harassment of animals strictly for media ends, and that’s something I decided not to allow to happen. If it’s for research, and if interaction with animals is necessary in order to do the research, that’s a risk worth taking. Simply put, when we’re interacting with animals, there must be a level of additional ethical responsibility.

You came back to Stony Brook a couple of years ago as a visiting scholar. What are your perceptions of SoMAS today compared to what you saw as a student?

You guys have grown incredibly. The whole department (and university) is so much more diverse and robust than when I was here. That’s not to say that it wasn’t at that time; after all, the Marine Science program was considered one of the best coastal oceanography programs in the country. It’s been terrific to see the growth, the further investment, and the dedication to the fundamental principles of conservation and sustainability. It’s exciting, and important, and I’m thrilled to be a part of it.