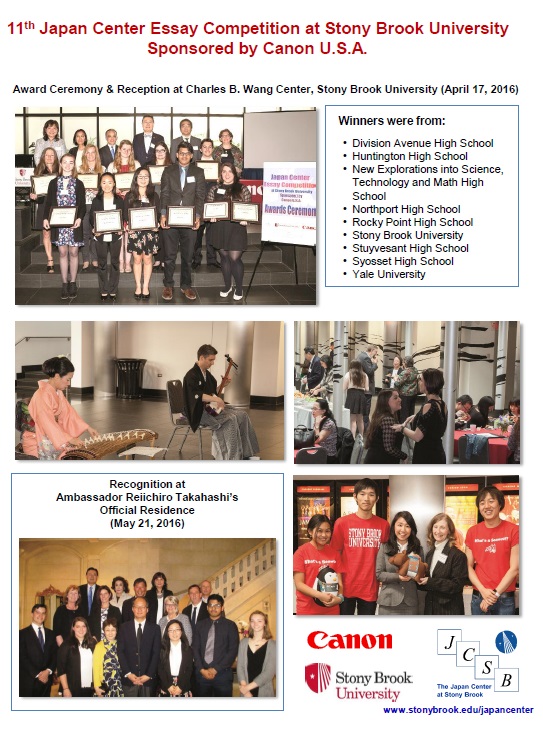

Award Winners

High School Division:

1st Place Best Essay Award and Consul General of Japan Special Award

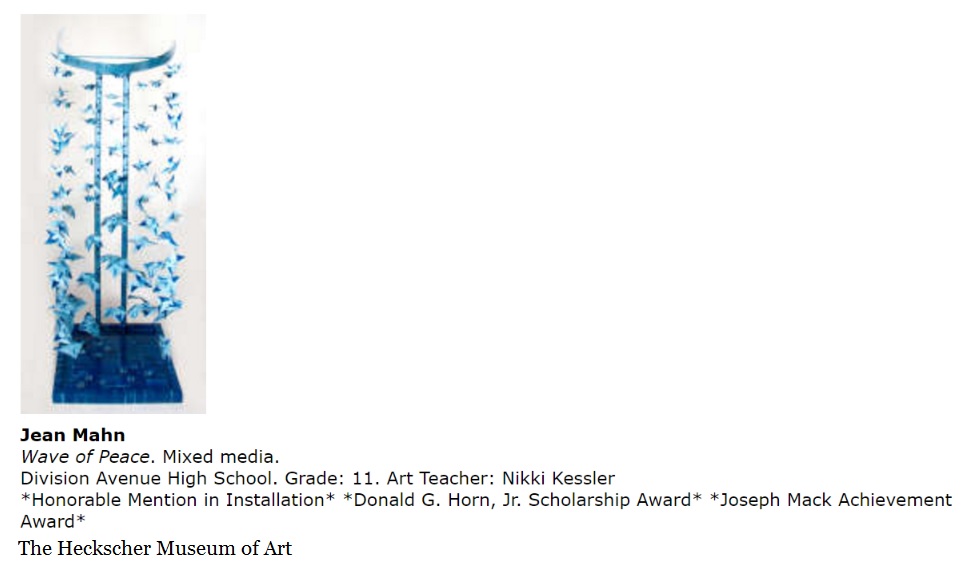

Wave of Peace by Jean Mahn (Division Avenue High School)

2nd Place Best Essay Award

Hope in Anguish: A Study of Names by Shaikat Islam (Stuyvesant High School)

3rd Place Best Essay Award

The Secret to Anti-Aging by Miho Horigome (Syosset High School)

College Division:

Best Essay Award

"Kuuki O Yomu": The Complexity of Keigo by Mizuho Yoshimune (Yale University)

High School and College Combined:

Uchida Memorial Award

Hayao Miyazaki's Exploration of Social Issues by Claire Shapiro (Rocky Point High School)

Merit Award

Ikebana: An Upbringing by Louis Herman (Rocky Point High School)

Japanese Hospitality: How Kindness Led to a Significant Personal Change by Tiara Hess (Stony Brook University)

My Dream in Tokyo by Elizabeth Hughes (Huntington High School)

Irezumi- East to West by Anita Maksimiuk (New Explorations into Science, Technology and Math High School)

A Lesson in Humility: Respect in Japanese Culture by Olivia Poplawski (Northport High School)

Finalists

Nick Brenner (Bard High School Early College Manhattan)

Julia Eng (Stony Brook University)

Joice Im (Binghamton University)

Israt Jahan (Stuyvesant High School)

Cezanne Lojeski (Earl L Vandermeulen)

Stanislava Rodionova (Bard High School Early College)

Lina Takemaru (Ward Melville High School)

Semi-finalists

Griffin Bluemer (Huntington High School)

Paolo Duran (Lynbrook High School)

Merrick Eng (Staten Island Technical High School)

Erica Farsang (Hicksville High School)

Bhavika Garg (Bethpage High School)

Sierra Block Gorman (Bard High School Early College)

Christina Jacob (New Hyde Park Memorial High School)

Asli Kizilkaya (Smithtown High School West)

Pridha Kumar (Townsend Harris High School)

Morgan Lafont (Garden City High School)

Ana Lainez (Wyandanch Memorial High School)

Michelle Lainez (Wyandanch Memorial High School)

Mariska Lalsingh (Townsend Harris High School)

Emely Lopez (Huntington High School)

Zoe Martin (Bard High School Early College Queens)

Connor McNeill (Garden City High School)

Diego Milla (Kingston High School)

Claudia Motley (Copiague High School)

Max Robins (Huntington High School)

Vanessa Yu (Oyster Bay High School)

Award Winning Essays

Who could have imagined that a 12 year old, who died of leukemia in Japan just after World War II, could have inspired ordinary Americans walking through a museum in Huntington, NY, sixty years later to view student artwork and quietly reflect on life and death, on war and world peace.

At six a.m. I gathered my belongings and set out into the cold for high school. Once at school, my teacher received permission to open the building so far before the school day began.

Inside, we worked with the efficiency of an assembly line. I exposed the sun paper to ultraviolet light, unfolded the cranes, developed the paper in water, set them out to dry, and refolded them into multi-toned blue birds. This was my routine from November until March, when my artwork was due to be submitted into the “Long Island’s Best Young Artist Competition.” Once I had created as many cranes as possible, I needed help in building a frame large enough to support my vision of a “Wave of Peace.” I asked my school custodian and he agreed to help. I stayed late after school for weeks learning how to do things I never believed I was capable of. I learned how to bend metal, create liquid glass, and saw wood. The last step was to string together the cranes, as they appear to open from one tightly folded crane to an open sheet of dark and light blue sun paper. Then, once I had enough lines strung up to the frame, I would line the poles and base with the exposed paper and fill the bottom with liquid glass and folded cranes.

This process, although seemingly drab and mechanical, consumed my thoughts and invaded my dreams, filling countless sheets of paper sprawled upon my nightstand. The history behind this project was so rich. I could not wait to complete my vision.

I conducted my own research, deducing which exposure time would best suit my little birds. As work progressed, these birds became a living part of me. I feel them still, their essence engrained in me. It is as much a part of me as the heart that beats inside of me. I cannot detach myself from the implications of the cranes. They simultaneously express peace and destruction, hope and loss, human nature and a certain otherworldliness.

Still, this accomplishment would not be possible without the custodian’s patience, my mother’s willingness to stay up all night developing paper, my teacher’s selflessness in arriving, uncompensated, to school early, and my friend’s support.

All of this time was dedicated to honoring one little girl, Sadako Sasaki. This Japanese girl contracted leukemia after the atomic bombing in Hiroshima. Japanese legend states if one folds one thousand paper cranes, one will be granted a single wish. Sadako folded cranes until she died at number 644. Before her death, she selflessly wished for world peace. In honor of her wish, I created a work so large and symbolic it was able to represent the magnitude of selflessness in her soul. Her kindness and my hard work formed my entry into the competition, which was not only accepted for display at the Heckscher Museum, but also won three awards.

Though I received much recognition for my sculpture, it has taken a while for me to truly understand what this has meant to me.

An important part of growing up is learning from life’s experiences.

I learned that sometimes from pain and anguish comes strength and compassion.

I learned that everyone matters.

I learned that hard work is sometimes its own reward.

And most amazingly, I learned that no matter how much, or how little, time we are given here on Earth, every one of us can leave a positive impact on the world.

The idea that the simple act of folding a paper crane could connect two people (from a different time, culture and generation) is beautiful and gives me hope that Sadako’s “Wave of Peace” can transcend borders, belief systems, and cultures.

Mine should not be the sole name on the recipient label. It should be addressed to those who made this fusion of culture and world events possible; my family, friends, teachers, and most importantly Sadako Sasaki.

Hope in Anguish: A Study of Names by Shaikat Islam (Stuyvesant High School)

My last name. Five letters. Two vowels. This, according to some, is the overwhelming problem with the world.

1.6 billion people follow my last name.

A few of them are terrible people. A few of them destroy its moral fabric to encourage their own futile, fatal ideals.

But the rest, in my experience, are peace loving, hard-working, ordinary, people.

On September 11th, 2001, many people learned my last name. On September 12th, 2001, they learned to despise it.

My last name means peace.

My last name means purity.

My last name is ISLAM.

I am 8 years old when I start to become uncomfortable wearing my taqiyah (skullcap). I fear others will despise me for wearing it, ridiculing me for following the so called ‘terrorists’. I decide to not wear it in public anymore.

I am 12 when SEAL Team Six kills Osama bin Laden in Abbottabad, Pakistan. My classmates ask my Sikh friend how he feels about his father dying. They ask me the same. I ignore them.

I am now 16 when Donald Trump justifies the use of identification for Muslims in the United States. Neuroscientist and presidential candidate Dr. Ben Carson justifies the death of Middle Eastern children in war. Islam is a bad religion. Islam is a terrible religion. Islam is a death cult. This is what the candidates say.

Funny thing is that I don’t remember signing up for any of that.

II.

It takes on average, around 5 seconds to sign one’s name.

On February 21, 1942, Franklin D. Roosevelt carefully pens his signature. This was an action on average, performed by him 307 times per year in the span of 12.12 years until his death in office. Shrouded by dense legalese and references to arcane laws and statutes, this document was very similar to the 3,217 executive orders that President Roosevelt would authorize during his presidency. Titled Executive Order No. 9066, the document signed in around 5 seconds would mean four years of internment—four years of harshness and deliberate alienation—for some 110,000 Japanese-Americans.

In the eyes of the general public, No. 9066 was legitimate. Years of being fed anti-Japanese propaganda would prepare the public for the entrée of internment. After December 7th, 1941, hadn’t the Japanese become subhuman, magically growing fangs, horns, and a debilitating lisp overnight?

After all, hadn’t Superman, the indestructible, unstoppable, bastion of American morality told children that they could ‘slap a Jap with war bonds and stamps!’ in Action Comics No. 58?

Captain Marvel swatted the Japs!

Popeye the Sailor Man destroyed the Japenazis!

Captain America teamed up with the Human Torch to defeat the ‘Yellow Peril’ in the Den of Doom!

Of the 110,000 Japanese-Americans incarcerated, 30,000 were subhuman, spying, enemy-combatant, ‘jap’, fanged, horned, yellow-peril…children. The ten camps were decrepit; in some instances, horse stables were refitted for human use. Medical care was terribly inadequate, creating the deadly farrago of dysentery, malaria, asthma, cancer, and vascular disease for inmates.

The mental and physical degradation would best be encapsulated in one phrase, used most commonly by interned families: shikata ga nai—helplessness.

Of these 110,000, none were ever convicted of treason or espionage.

It takes around 5 seconds for someone to sign their name.

It takes decades of patience to forgive one.

III.

When General John L. Dewitt ordered the removal of the Japanese into camps, Fred Korematsu refused. Korematsu hid. Having been found by authorities, Korematsu was convicted of disobeying military orders; as a result, his family and he were forced to relocate to the Topaz War Relocation Center. The conditions, said Korematsu, “were worse than jail.” After his release, Fred Korematsu would be silent for three decades, never talking about his internment to anyone ever again.

On November 10, 1983, Judge Marilyn Hall Patel removed Korematsu’s conviction of five years when Professor Peter Irons of UCLA San Diego found evidence detailing the deliberate misuse of FBI and military intelligence that found Japanese-Americans were no real threat to national security.

At the trial, Korematsu famously said, “If anyone should do any pardoning, I should be the one pardoning the government for what they did to the Japanese-American people.”

In 1998, Korematsu won the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Until his death, he would work arduously to maintain civil rights in the United States. No one would be subject to the injustice he faced. One of the groups he worked to protect were Muslims.

Kibo. Hope.

Works Cited

"About Fred Korematsu." Fred T Korematsu Institute. N.p., 23 Jan. 2009. Web. 07 Jan. 2016. <http://korematsuinstitute.org/institute/aboutfred/>.

Chin, Steven A. When Justice Failed: The Fred Korematsu Story. Ed. Alex Haley. Raintree, 1992, p. 70.

"Donald Trump's Horrifying Words about Muslims (Opinion) - CNN.com." CNN. Cable News Network, n.d. Web. 07 Jan. 2016. <http://www.cnn.com/2015/11/20/opinions/obeidallah-trump-anti-muslim/>.

"Historical Overview of the Japanese American Internment." Historical Overview of the Japanese American Internment. N.p., n.d. Web. 07 Jan. 2016.

"Japanese-American Relocation." History.com. A&E Television Networks, n.d. Web. 07 Jan. 2016. <http://www.history.com/topics/world-war-ii/japanese-american-relocation>.

"When the Emperor Was Divine Paperback – October 14, 2003." Amazon.com: When the Emperor Was Divine (9780385721813): Julie Otsuka: Books. N.p., n.d. Web. 07 Jan. 2016.

© The Japan Center at Stony Brook

http://www.heckscher.org/pages.php?which_page=exhibition_more_images&which_exhibition=123

The Secret to Anti-Aging by Miho Horigome (Syosset High School)

“Hi, how are you today”

“Fine, thank you baba”

The sparkle in my grandmother’s eyes shined with satisfaction as she once again successfully greeted me in English. She appeared to be unchanged from years before, but her slightly hunching back seemed to bother as she continuously patted it. To my surprise, her old age was not reflected upon her skin. No wrinkles, her face seemed flawless than years before.

“Oh, there’s my beautiful granddaughter!”

My grandfather’s wide smile grew humongous, clearly showing his anticipation and joy for this moment. Like grandmother, he too was unchanged except for his slightly dissipating hair, which seemed to have accumulated in its loss. Regardless of his hair, however, his darkly tanned face also lacked wrinkles. Maybe the stereotypical “Asians don’t age” phrase was true in their town.

The first time I met my grandparents was four years ago when they came to visit my house in America. Because of certain circumstances, I would never be able to see my grandparents unless I went to Japan. I feared traveling alone but the longing to visit my grandparents overwhelmed me, and so, I arrived at Japan with high hopes of experiencing my lost culture through them.

After two hours of gossiping with my grandmother, the humid Nagano air started to induce a lot of sweating.

“Okay, I think that’s enough for today! Go hurry and wash up before the rush hour comes!”

Hurry? Rush hour? I had never heard those words put together in a sentence with bath.

“Baba, where is your shower room?” I asked bewildered. Then, from the other room, I heard my grandfather shout,

“Oh, we don’t have a shower room! Just go to that public onsen bathtub around the corner.”

My heart stopped. Public bathtub? Never in my life had I gone completely gone naked in front of others to bathe. Just the thought of it made me nauseous, but what other choice did I have?

I turned the corner and encountered a steel building that had two doors: a woman's and a men's. I slid the key and opened the door. A boiling breeze of water vapor clouded my glasses and the smell of chemical filled my nose to deepen my displeasure. As the clouding disappeared I noticed that nobody was there, so I quickly took off my clothes, and entered the tub room. Almost immediately I started to sweat from the burning vapor the water was giving off, but my thoughts were on how fast I could get out of this place. Yet when the water touched my skin, I was mesmerized. This water that my grandfather called onsen was clearly higher in temperature than normal bath water but it felt much softer on my skin. Seconds later, a woman about the same age as my grandmother entered the room. She too had no wrinkles. After quickly washing her body, she entered the tub. Until then I never noticed the stairs going into the tub. Surprised and curious, I stuck one toe into the water and shrieked in burning pain. The elder woman chuckled.

“Just go in. You’ll get used to it.”

I blushed in embarrassment and went in, ignoring the pain of my flesh burning off. Few seconds later, I noticed my red skin lessening in pain and was overcome with a soothing sensation. Every tense muscle loosened up and I was comfortable enough to start a conversation with this woman. I made a new friend that day and in those few hours, I forgot about all my problems.

At the end my first onsen experience, I skipped out of that public bath feeling revived and content. At my return, my grandmother acknowledged my invigorate appearance.

“Your skin looks lightened and smoother!”

I realized then that my skin was actually healthier and younger than before. Then it clicked: my grandparent’s flawless skin was because of this onsen water. My hypothesis was correct as my grandparents explained this phenomenon. This water was actually heated by active volcanoes and contained various minerals that helped relieve the body from various undesired problems.

I left Nagano that summer with a new mindset. What I learned that day was not just an understanding of my grandparents, but also the impact of cultural shocks. Onsen plays an important role in health, relaxation, and bonding experience that can never be attained through the American culture. I knew right away, that I would be visiting them again very soon.

© The Japan Center at Stony Brook

"Kuuki O Yomu": The Complexity of Keigo by Mizuho Yoshimune (Yale University)

Every day in kindergarten, “story time” was an exciting time of the day. Kevin, my kindergarten teacher, would put on his dark green “story time” robe and sit in the rocking chair at the front of the room with a picture book to read aloud to the class animatedly. He was very tall, had long, red hair in a ponytail, and wore perfectly round glasses that gave him an owlish look. To top it off, he wore dangling fish earrings that moved in sync with his head movements. During these story times, we would sit cross-legged on the rug, forming a semi-circle around Kevin’s rocking chair, leaning forward eagerly to hear the story of the day. We would always be asking him questions like, “Kevin, why was the frog able to get out of the bucket?” or, “Kevin, can we make stone soup?” or “Can I take this book home, Kevin?” At my elementary school, students called their teachers by their first names, and so no one referred to Kevin as Mr. Zilber – it was always “Kevin.”

For me, being born and raised in New York, this was the normal elementary school experience. However, as I grew up and began to take more interest in studying Japanese and the culture, I soon realized that this casual classroom setting at school was not the norm in Japan. I had been aware of the importance of using keigo (the polite form of speech in Japanese) when meeting someone for the first time or when speaking to someone who is older. However, it was finally in college when I began to study Japanese intensively that I became more exposed to and also fascinated with the complexities of keigo. As my professor explained in detail the countless nuances within keigo, including the differences between sonkeigo, kenjōgo, and teineigo (honorific, humble, and polite languages, respectively), it began to intrigue me how deeply ingrained keigo is in not only the Japanese language, but also in its culture and society. Questions raced in my head, as I wondered: how would one use keigo when interacting with Japanese students of the same age? Not using keigo at all seemed narenareshii (unnecessarily friendly) even when talking to others of the same age, but always using keigo also seemed too katagurushiii (too stiff and formal). How does one gradually lower the wall that keigo creates? Is this something that young people in Japan also struggle with as well?

As a member of the Japanese-American Student Union (JASU) at my school, I had the opportunity to experience this unique complexity of utilizing keigo first-hand through a special collaborative project between my school and a group of university students from Tokyo. Since 2014, JASU at Yale University has joined efforts with the Knowledge Investment Program (KIP) from Japan to hold joint symposiums on some of the major social issues of Japan. During these few days, JASU and KIP students interacted in both Japanese and English; on the first day, we used keigo when we conversed with the KIP students in Japanese, adding “desu” or “masu” to the endings of words as a formality. On the contrary, when we all spoke in English, the formality wall seemed to disappear immediately. By the end of the third day, however, when we were saying our farewells, all our Japanese conversations were in casual speech, as though we had known each other for three months instead of just three days. Looking back, it is hard to pinpoint the exact time in which the formalities of keigo softened and transitioned into casual speech, but it was undoubtedly with the help of, as it is often said in Japanese, “kuuki o yomu,” which translates to “reading the atmosphere.” As we got to know each other better, we were able to gradually lower the formality walls in response to the other person’s reactions, which is essential in any interaction regardless of the language.

The JASU-KIP collaboration was my first time that I got to know students from Japan around my age, and it was a truly memorable and valuable experience in grasping how keigo is used in various social situations in Japan. From a larger perspective, I came to understand how the incredibly sensitive nature of the Japanese language also reflects the importance of respecting and valuing others. As a Japanese-American, I used to see it as a challenge to balance the two cultures, but now, I feel grateful that I can experience them both at the same time.

© The Japan Center at Stony Brook

Hayao Miyazaki's Exploration of Social Issues by Claire Shapiro (Rocky Point High School)

Hayao Miyazaki once said, “I do believe in the power of story. I believe that stories have an important role to play in the formation of human beings, that they can stimulate, amaze, and inspire their listeners.” Since I was a child, Japanese animation has had a significant influence on my life. My older sister and I would watch Studio Ghibli films over and over. One of the most well known and influential film makers and my personal favorite, Hayao Miyazaki, amazed me with fantastically vivid worlds filled with magic and adventure. Spellbinding stories inspired me and helped me grow as a person. The skillfully crafted artwork and beautiful soundtracks that are characteristic of Japanese animation enchanted me and I fell in love with every aspect.

Behind the vibrant, stunning landscapes, cultural motifs, and the profound and fascinating characters of these movies lies a deeper meaning. Hayao Miyazaki, and other Japanese animators, typically integrate a moral lesson into their stories so that they may influence others to think a different way. Hayao Miyazaki uses animation to promote themes of feminism, pacifism, and environmentalism. Perhaps my favorite Miyazaki movie out of all of them is Princess Mononoke. Masterfully crafted, the film ties together all of Miyazaki’s prominent themes into one cohesive and fluid work. This film presents two strong female protagonists fighting for what they believe is right in a battle between humans and nature. I believe that this lends itself to our current situation in the real world. With this film Hayao Miyazaki promotes awareness of not only the destruction of the environment caused by humans, but the destruction that our actions will bring unto us. As a child I was too young to understand his life lessons, however, I understood at least one thing; the world is beautiful and full of magic and it is my decision whether to believe that or not. Neither my parents, nor my teachers, nor any adult has the ability to change how I see the beauty in this world. The fact that he is able to incorporate such a theme into a film and still show children that the world is beautiful and full of magic is what truly makes his movies fantastic.

Miyazaki’s movies have inspired me to see the world in a different way, have moved me to be independent and courageous. The strong female characters in his movies don’t need a man to save them, instead they are able to find companionship and a supporter in each other. Today I am proud to be a woman even though some might consider it a disadvantage. Hayao Miyazaki tells children they can accomplish anything they dream of regardless of gender or age. His films made a young girl see the beauty and magic present in the world and he taught her what it means to be human and have connections with others and the world around us. Studio Ghibli’s films contain Japanese culture and has introduced many around the world the Japanese ideas and customs. I have been inspired to learn more about Japanese culture and I am currently studying the Japanese Language in an effort to experience Japanese culture on a different level. His movies truly mean a great deal to me and I’m grateful that I have learned more about the world and Japanese culture through his animation.

Bibliography-

Rieko Okuhara, The Looking Glass: new perspectives on children’s literature,http://www.lib.latrobe.edu.au/ojs/index.php/tlg/article/view/104/100, N.P, 2006. Web. January 6, 2016.

Baseline, “Hayao Miyazaki”, The New York Times, http://www.nytimes.com/movies/person/167694/Hayao-Miyazaki/biography, 2010

© The Japan Center at Stony Brook

Ikebana: An Upbringing by Louis Herman (Rocky Point High School)

When I was about three years old, I came home from school one day holding a paper cup with a flower inside it. When my mom asked me what it was, I looked at her like it was the most obvious thing in the world and said, “ikebana.” I’d learned about the Japanese art of flower arranging in my preschool class, somewhere between singing Baby Beluga and playing duck duck goose, because I have been lucky enough to spend nearly half my life outside the United States, and because this particular preschool just happened to be located in Tokyo, Japan.

For as long as I can remember, Japan has been a presence in my life. My earliest memories–learning to ride a bike, trying my first puff pastry, going to Legoland–are all from the eighteen months I spent there, but even after I moved back to Long Island, the country was still in my life. I took saturday morning Japanese lessons, went on day trips with my family to the Mitsuwa department store in New Jersey, and even had a framed picture from the opening of Tokyo DisneySea over my bed.

As I got older, my family made it a point to never go longer than a couple of years without going to Japan. We went all over–Nara, Hakone, Osaka–to the point where I'm more comfortable in the Tokyo subway than in the New York City one. They always had their favorite spots–as did I–but every trip still felt fresh, largely because each time we went, we made sure to try at least one new thing. At first, it was little stuff–a new ride at Disneyland, a hard-boiled egg by the Hakone hot springs–but as I grew older and developed my interests further, we branched out more, visiting new cities and exploring historical sites like Osaka Castle and the Golden Pavilion.

That was just how I grew up. I moved from Long Island to Hong Kong when I was ten, going to an international school from fifth to eleventh grade. The experience really shaped me into the person I am today, fostering the spark of adventure and the willingness to leave my comfort zone that my family trips to Japan had already instilled in me. Because of this intercontinental upbringing, I've never really had a solid sense of what the word "home" meant to me.

Basically, it's everything and nothing. It's my apartment in Hong Kong and my backyard in Oyster Bay and the view from the top of Osaka Castle, when the morning fog clings to the skyscrapers and you feel like you're in a fairy tale. It's the pottery shop by Jindaiji Temple and the Buzz Lightyear ride at Tokyo Disneyland and the big tree outside my house that I nearly broke my leg trying to climb and a thousand other memories, of last goodbyes and first hellos and passport stamps.

And, in the end, Japan was the catalyst for my placelessness. It's where my sister was born and where I attended my first school, and leaving there was the first time I'd ever had to say goodbye.

Coming to America, though, was my first fresh start. I made amazing friends at my school and enjoyed the time I had with them before doing the same in Hong Kong. In the last seventeen and a half years, I've lived in four completely different places, having to start fresh with each move, and I love it. I love the rush of excitement before my first day at a new school, when I'm just thinking about all the people I'm going to meet and the friends I'll make. I love the chance to meet new people and try new things, and I love Japan for teaching me how to say goodbye–if only because, in doing so, it taught me to say hello.

© The Japan Center at Stony Brook

Japanese Hospitality: How Kindness Led to a Significant Personal Change by Tiara Hess (Stony Brook University)

It was in December of 2010 that I took my first adventure outside of the United States. Destination: Tokyo. From the stewards and stewardesses aboard the plane, to the officials at Narita airport, everyone was kind and welcoming. When dealing with the nature of Japanese hospitality, I was awestruck. If there was any culture shock at all, it came in the form of kindness. The workers loading and unloading the limousine buses would bow to the vehicles before they departed. The staff at the hotel I stayed in went above and beyond with any questions or concerns I might have had. Coming from New York, I would say there was a huge difference in how the Japanese express hospitality, and that was something I greatly appreciated, so much so that I cried when I landed in JFK Airport—the bathrooms were dirty, everyone was grumpy, and there was no organization; I missed Japan.

Years later I returned to Japan on a study abroad program. I was a participant in the Mishima homestay program in the summer of 2014, and was both excited and nervous for what would lie ahead of me. These fears soon disappeared after I became extremely ill during my first week on the program. My host mother barely spoke English, and I barely spoke Japanese, but we found a way to communicate during my stay. When I became ill, I was worried that I would burden her, but that familiar warmth assuaged any fears. She went to the convenience store for me, buying me things that would help me to feel better. When I apologized profusely, she looked at me and remarked in English: “It’s okay. You are my daughter.” Thanks to her hospitality, as well as the kindness of everyone involved with the study abroad program, it was easily one of the best months I’ve had in my life. A woman whom I barely knew had opened her home to me and was now taking better care of me than my own mother did. I knew then that this woman, and her family, would be a part of my life forever; in much the same way, Japan has always been too.

This past summer, for instance, I interned at Japan Society in Manhattan. I’m a part of an International Relations Scholarship program called the Jewish Foundation for the Education of Women. This program requires each participant to secure an internship in NYC for the summer between our junior and senior years. I vied for Japan Society because I truly supported their mission, which is to deepen the ties between the US and Japan in a multitude of ways. I wound up applying to the Business and Policy department, and it led to an incredible summer (again)! The hospitality I felt at Japan Society was unbelievable. On the first day, I met everyone in the office; I would have even met the President had he been in. I felt like I was part of the team; everyone was willing to help one another so that the goals of each department were met, and the clients were treated with so much respect. I was half an hour early every day because I enjoyed being there so much! The entire climate of the office was different than any feeling I’ve had working for an American company, and I’ve held various jobs at different levels within assorted companies. In all of these positions, the feeling that came from the bosses was one of intimidation, and as an employee you were always wrong, unless it was in a dispute with the customer—because we were taught that the customer actually wasn’t always right. Clients would be mocked behind their backs, and a fair amount of sarcasm was often applied in many instances of working with customers. This was the corporate culture I was acclimated to; it’s no wonder then that I felt incredibly heart-warmed by Japanese practices.

All of my experiences with Japan have culminated in my feeling a deep sense of respect for its hospitality, warmth and kindness. It took me a few years to realize just how big a part of my life Japan has been. In reflecting on all of these experiences, I have even changed my future plans and goals around, and will be applying to graduate school to further study Asian Studies with a focus on Japan. This feeling keeps drawing me in, and I finally think I’m ready to explore it in an academic setting.

© The Japan Center at Stony Brook

My Dream in Tokyo by Elizabeth Hughes (Huntington High School)

It was a chilly winter day in Huntington New York, my hometown. Being a Friday night, my friends and I were eager for our dinner at Kashi, a Japanese restaurant in the village. We indulged in sushi for hours and soaked in all the culture around us. That night I stayed up reading all about japan online. When I finally fell asleep hours later I had suddenly landed in Tokyo! Confused, but however excited, I jumped out of my bed in Tokyo. I looked around in search of some clue as to what was going on but all I found were my parents. I asked my mother why are we here? And she shushed me and told me I must get to school before I was late. “Go on now, your father will drive you!” she exclaimed. I walked out of our apartment building's door and found myself in a frenzy. Honking cabs, the sound of many voices, smells of sushi and such. My dad’s Prius pulled up and he dropped me off at my all-girls school. It was much different than schools in America.

Upon entering i was greeted by my friends, they were studying intensely for our math test, soon the bell rang for homeroom to begin. We traded in our street shoes for our school slippers, and made our way to class. I was then informed of a school trip our class was taking later that day. We were headed to the Tokyo Disneyland! I was so excited, because not only would i be experiencing great Japanese culture, but i would be going to Disney! My friends and I tidied ourselves up and we took the train to Disneyland. We got on the train and we were off! The train ride would be about an hour long we were informed of. So I decided to dose off with my friends. About an hour later my friend Kim and I woke up, and much to a fright, we couldn’t locate a single classmate of ours, or our teacher! Kim and I asked the conductor when the stop for Disney would be, he told us it was about 3 stops ago! We panicked and got off the train as soon as possible. We were in the middle of Tokyo! I had no idea where I was but Kim assured me we’d find our way. A boy around our age asked us if we needed assistance since we looked lost., his name was Akio. We told him what had happened to us and he said instead of going to Disney, he’d be our tour guide around the city and show us the real culture of Japan. Kim Akio and I headed off, first we visited the Meiji shrine. I remembered learning all about the Meiji Restoration in Global class. I loved it! It was so beautiful, every single detail was perfect. After admiring this beautiful structure, we headed off to lunch. Akio took us to the best sushi place in town. We indulged for about an hour then we headed off to odaiba and the rainbow bridge. I had never heard of this before, but he told us it was an artificial island built in the middle of Tokyo bay. We learned tons about the history of this little island how it was built for defense, but now a public park. We spend tons of time there soaking up the culture. By then it was dinner time. We were having so much fun we did not realize that our classmates were probably searching for us. We thought about heading back, but we resisted. We went to dinner, and then we proceeded to the Tokyo sky tree. Akio told us so much about this tower. Not only was it a broadcast station for many popular networks, but it was also the tallest building in Tokyo. I couldn't believe how beautiful it was, the tower was lit up purple. After spending sometime here, we realized how late it was. We thank Akio for his help and for a great day and headed back to school.

Then suddenly I awoke. I was so upset to find that it was only just a dream. After this I was so intrigued by Japanese culture, and all the wonders of it. For a while I begged my parents to visit Tokyo, they weren’t fans of planes so they said no. After this I studied as much about Japan as I possibly could.

© The Japan Center at Stony Brook

Irezumi- East to West by Anita Maksimiuk (New Explorations into Science, Technology and Math High School)

I got my first tattoo because, at age sixteen, its permanence felt dangerous. I was developing a confidence I'd never had before, and watching the foreign black ink become a part of me made me feel real, like I was finally ready to tear into the world. I began to believe in my capabilities as an artist and a writer, and my new tattoo was right there, reminding me that I was alive. A few months later, that same confidence and newfound sense of self drove me to apply for a writing position at a burgeoning arts and lifestyle website called highlark.com. I am now a staff writer for the site, and each week, three of my articles are published online. I write about contemporary artists, which include illustrators, painters, musicians, muralists, and, my personal favorite, tattoo artists. It's through my work with Highlark that I discovered the art of Irezumi.

Irezumi is the term for traditional Japanese- style tattooing, known for its large-scale design and nature motifs. In Japan, tattooing was for centuries a form of punishment; criminals would receive markings on their faces and elsewhere to humiliate them in the eyes of society. However, during the Edo period, which commenced in the 1600's and lasted until the late nineteenth century, Irezumi became a legitimate expression of creativity. Tattoo artists across the islands began to render intricate illustrations full of symbolism and traditional imagery. These tattoos immortalized Japanese folklore, featuring animals, religious symbols, legendary heroes, and mythical creatures. In the early 1900's, because of their shocking beauty and outlaw nature, Irezumi tattoos became a staple of the Yakuza, the Japanese equivalent of organized crime, which only added to their already negative connotation. A typical Yakuza piece would have covered the entire back, curling over the shoulders and onto either side of the torso. Though tattooing has been legal in Japan for decades now, it is still largely stigmatized in Japanese society, and retains its negative connotation. Most artists work privately, only by appointment, and many establishments will not serve tattooed customers. However, in the west, Irezumi has a very different reputation.

Here, Japanese tattoos have skyrocketed in popularity, mostly because of their visual appeal. This has undermined the traditional value of Irezumi imagery, which is prone to misinterpretation by tattoo artists and customers alike. It is not uncommon to see someone sauntering down a Manhattan street sporting a freshly inked koi fish on their bicep, completely oblivious to the fact that downward- facing koi are a traditional symbol of inability to overcome obstacles.

As a member of the highlark.com team, I have been lucky enough to write about Irezumi artists that uphold an incredible respect for the Japanese culture, despite their various ethnic backgrounds. These artists give quality tattoos based on a comprehensive understanding of traditional imagery and the values behind it. Unfortunately though, in a society that values aesthetics as highly as we do, cultural context is often overlooked in favor of trends. After being exposed to the thriving western subculture around Irezumi art, I myself have gained a deeper understanding of Japan's culture, how it compares to that of the United States, and how tattoo art is received across the world.

Though Irezumi employs traditional motifs and narratives, it is still regarded with suspicion in its place of origin. Its negative reputation is far older than its relatively new identity as an art form. In the west, it has been adopted, by some, as a decorative statement- eye candy meant for nothing more than visual allure. Some artists recreate Irezumi technique because they know how high customer demand is, while others study its underlying symbolism for years before delving into the craft. When I become a practicing artist, I am going to seek inspiration in the art of cultures other than mine, but I am going go do so with an utmost respect in order to maintain cultural integrity. Art is a vessel for communication, preservation, and interaction between cultures, and it will always be interpreted in various ways. As long as I cultivate a certain level of awareness, I am free to discover the creativity of other cultures just as I discovered the unassuming beauty of the art of Irezumi.

© The Japan Center at Stony Brook

A Lesson in Humility: Respect in Japanese Culture by Olivia Poplawski (Northport High School)

The amazing thing about studying abroad is that there is so much that can be learned in a short period of time. Throughout my one month home stay in Japan, not only was I embraced by a second family, but I received priceless wisdom concerning respect and humility by participating in the everyday Japanese family dynamic.

In the Japanese language, many common phrases have several variations, each with a different application. Even the word “please”, a straightforward sentiment in the English language, has three common variations in Japanese. My experience using and hearing this word in Japan made it clear that each translation is linked to an aspect of respect and humility, two central values in Japanese culture.

My first day of school in Japan was a whirlwind of excitement and indescribable experiences. Despite my confusion due to the dramatic time difference, my heart was racing with adrenaline, as I prepared to soak in every ounce of the thrilling new culture. From my perch in the last row of desks, it became clear that the students maintained a far deeper level of respect for their teachers than I had ever witnessed. The moment a teacher acknowledged the class, every student stood up and said “onegai shimasu” accompanied by a synchronized bow. I watched in awe as my host sister, Kaori,and classmates sat in near total silence, absorbing every drop of knowledge their teacher offered. “Onegai shimasu,” literally meaning “please do,” is used as a polite request. In the classroom greeting, the students are requesting the teacher’s wisdom, further evidencing the reverence held for teachers. I admire these classmates who honored their teachers rather than concentrating on their own achievements.

Arriving at the doorstep of my new home, I struggled to haul my bulging fifty-pound suitcase up the stairs. My ojiisan,meaning grandfather, rushed to assist me, carrying all fifty pounds of luggage to my room. Reflexively, I refused his assistance. With a warm smile, he simply said “douzo”, and continued to lift my heavy bags. “Douzo” is another translation of “please,” often used when insisting that someone accepts a gift or an act of service. I will never forget how this simple act of kindness made me feel like a part of my loving new family on the other side of the world. Elders are greatly respected in Japan, making my grandfather’s actions even more significant. By witnessing my elder’s selflessness and learning the high honor bestowed upon the guest in Japanese culture, I wanted to maintain an attitude of obedience, kindness, and selflessness in this new home.

Throughout my short stay in Japan, I built a strong relationship with my ojiisan. Grandparents play a major role in the Japanese family, with the father’s parents often living very close by. Every morning, ojiisan would join us for breakfast, greeting me with a friendly smile and a chipper “Ohayo!” His love for his grandchildren was evidenced by little sacrifices he made everyday. For me, the most impactful action he took was speaking with me in my language. Having only learned basic phrases and vocabulary terms, I still felt embarrassed with my limited knowledge of Japanese, often relying on, “Kudasai, eigo wa hanasemasuka?”, “Please, can you speak English?”. Most of my peers in Japan spoke English fluently, but the older generation spoke little English. Before I arrived in Japan, Kaori had mentioned that her grandfather was learning English in order to speak with me. I was so humbled to know that an elder would care that much just to communicate. When I met my host grandfather, I loved conversing with him, whether it was in my scrambled Japanese or in his beginner English. As soon as I let go of my pride and simply said “kudasai”, the word I’d been dreading the most, I finally understood him, and my relationship with my grandfather grew so much stronger. Admitting my weakness allowed me to grow to my full potential as an exchange student, learning from every situation and absorbing every piece of wisdom my host family could impart.

I will always look back on the beautiful example set by both my elders and peers in Japan, and remember how influential the values of respect and humility were in the everyday lives of my companions. By observing the emphasis placed on respecting elders, as well as the kindness which is shown to all people in Japan, I have learned the invaluable lesson of humility.

© The Japan Center at Stony Brook

-

See pagesabout

-

See pagescontact

-

See pagesevents

-

See pagesheart of japan

-

See pagesFiles

-

See pagesAssets

-

See pagesBackground

-

See pagesBanner

-

See pagesButtons

-

See pagesCover

-

See pagesPreloader

-

See pagesSkins

-

See pagesSounds

-

-

See pagesData

-

See pagesFscommand

-

See pagesJs

-

See pagesMedia

-

See pagesAnimation

-

See pagesAudio

-

See pagesBook

-

-

See pagesDownload

-

See pagesImage

-

See pagesImageanimation

-

See pagesSwf

-

See pagesVideo

-

-

See pagesPages

-

See pagesInteractive

-

See pagesLarge

-

See pagesMedium

-

See pagesSmartphone

-

See pagesSvg

-

See pagesTablet

-

See pagesThumbs

-

See pagesTiles

-

See pagesTranslate

-

See pagesWords

-

-

See pagesScripts

-

-

See pagesHtml5

-

See pagesJs

-

See pagesLibs

-

-

See pagesResources

-

See pagesIe

-

See pagesMedia

-

See pagesPlayers

-

See pagesSkins

-

See pagesNn

-

See pagesPp

-

See pagesSl

-

-

See pagesOffline

-

-

See pageslinks

-

See pagesAudios

-

See pagesJapanese

-

-

See pagesFonts

-

See pagesImages

-

See pagesTables

-

See pagesUtilities

-

See pagesScripts

-

See pagesJs

-

See pagesSlider

-

-

-

See pagesnews

-

See pagesprograms

-

See pagesuseful links

-

See pagesabout

-

See pagescontact

-

See pagesevents

-

See pagesheart of japan

-

See pagesFiles

-

See pagesAssets

-

See pagesBackground

-

See pagesBanner

-

See pagesButtons

-

See pagesCover

-

See pagesPreloader

-

See pagesSkins

-

See pagesSounds

-

-

See pagesData

-

See pagesFscommand

-

See pagesJs

-

See pagesMedia

-

See pagesAnimation

-

See pagesAudio

-

See pagesBook

-

-

See pagesDownload

-

See pagesImage

-

See pagesImageanimation

-

See pagesSwf

-

See pagesVideo

-

-

See pagesPages

-

See pagesInteractive

-

See pagesLarge

-

See pagesMedium

-

See pagesSmartphone

-

See pagesSvg

-

See pagesTablet

-

See pagesThumbs

-

See pagesTiles

-

See pagesTranslate

-

See pagesWords

-

-

See pagesScripts

-

-

See pagesHtml5

-

See pagesJs

-

See pagesLibs

-

-

See pagesResources

-

See pagesIe

-

See pagesMedia

-

See pagesPlayers

-

See pagesSkins

-

See pagesNn

-

See pagesPp

-

See pagesSl

-

-

See pagesOffline

-

-

See pageslinks

-

See pagesAudios

-

See pagesJapanese

-

-

See pagesFonts

-

See pagesImages

-

See pagesTables

-

See pagesUtilities

-

See pagesScripts

-

See pagesJs

-

See pagesSlider

-

-

-

See pagesnews

-

See pagesprograms

-

See pagesuseful links